Trauma Treatments

Treatment for trauma and stressor-related disorders

As with the majority of disorders, most people experience the greatest benefit from a combination of psychotherapy and medication. The pharmacological component may not be necessary for those with minimal symptoms. In addition, some individuals are very opposed to taking psychotropics or medication in general. However, when the symptoms are severe and persistent, it is possible that “talk therapy” alone will not be as effective.

Medication

Medication by itself is not likely to cure trauma- and stressor-related disorders, but it can help minimize the symptoms. For PTSD, antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs) have been found most effective, although they are not the only choice. Just as when they are used for depression, it is important to note that antidepressants may pose serious risks to children, teens, and young adults (including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts). Depending on the predominant symptoms—whether for PTSD, ASD, or an adjustment disorder—your medical professional may prescribe antidepressants or medications typically used for anxiety disorders, such as benzodiazepines, buspirone, or beta-blockers.

Ideally, any psychotropic drug should be prescribed after a complete evaluation by a psychiatrist, since medical doctors with a specialization in psychiatry are the most knowledgeable professionals when it comes to this type of medication. To find the latest information about medication, talk to your medical doctor and visit www.fda.gov.

Note: There is no “one-size-fits-all” psychotropic medication. You may need to try more than one medication before you and your doctor find the one that works best with your symptoms and causes you the fewest and least bothersome side effects.

Does Dr Maxwell prescribe medication? We get this question a number of times every year, so let’s clarify. In the state of Georgia (and most other states in the U.S.), the only professionals with the title of “doctor” who are allowed to prescribe any type of medication are medical doctors/physicians. The clinicians in the mental health field who have a PhD or a PsyD have the prefix of “Dr” because they hold academic doctoral degrees, not medical licenses.

Psychotherapy

First, here is a brief section on which approaches are typically used for each of the three diagnoses. Then, continue reading for a more detailed description of each approach.

For PTSD and ASD

The treatment of choice follows the so-called tri-phasic model (Phase 1: Developing resources for safety and stabilization; Phase 2: Trauma memory processing; Phase 3: Reconnection). Each phase has specific goals and treatment techniques. Approaches include cognitive-behavioral therapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy, and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). These approaches are also meant to treat any co-occurring conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.

For Adjustment Disorder

Approaches include cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy. In more severe cases, or for a disorder that persists, EMDR and Cognitive Processing Therapy may also be helpful.

When the main stressor is change, a good part of the treatment is spent on processing the accompanying factors such as uncertainty, ambivalence, doubt, and personal insecurities. Talking to a professional can help with a more thorough and realistic analysis of the situation, including what your alternatives may be, what can be learned from the change, how you can improve your coping and problem-solving skills, and how you can proceed while gaining inner strength and increasing your self-awareness.

Different Types of Psychotherapy Approaches

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

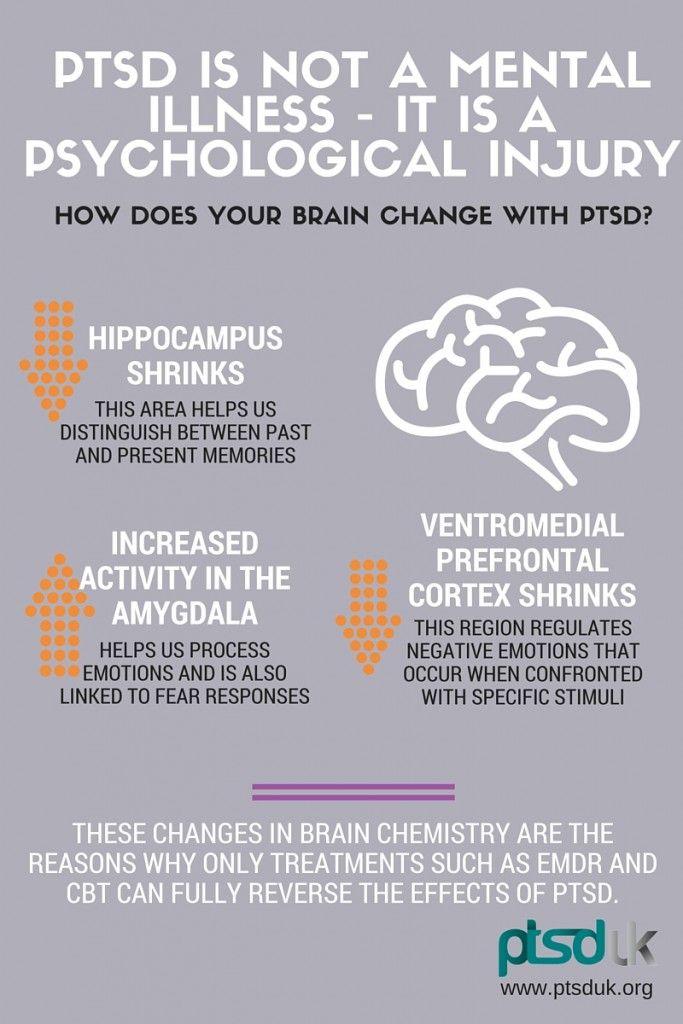

EMDR therapy is an integrative psychotherapeutic approach that was originally developed for the treatment of PTSD (which, as mentioned above, used to be categorized as an anxiety disorder). Since then, it has been proven effective for a number of other conditions. EMDR combines a specialized technique (bilateral dual stimulation) with components of CBT and psychodynamic therapy. Click here to go to the EMDR page on this website.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is known for its emphasis on practical, step-by-step tools and psychoeducation. In general, it is used to identify and challenge negative beliefs and emotions that contribute to the maintenance of the disorder. CBT includes psychoeducational handouts, weekly action plans, weekly logs, and worksheets—all with the goal of helping you unlearn dysfunctional responses and learn new ways of reacting through repeated practice.

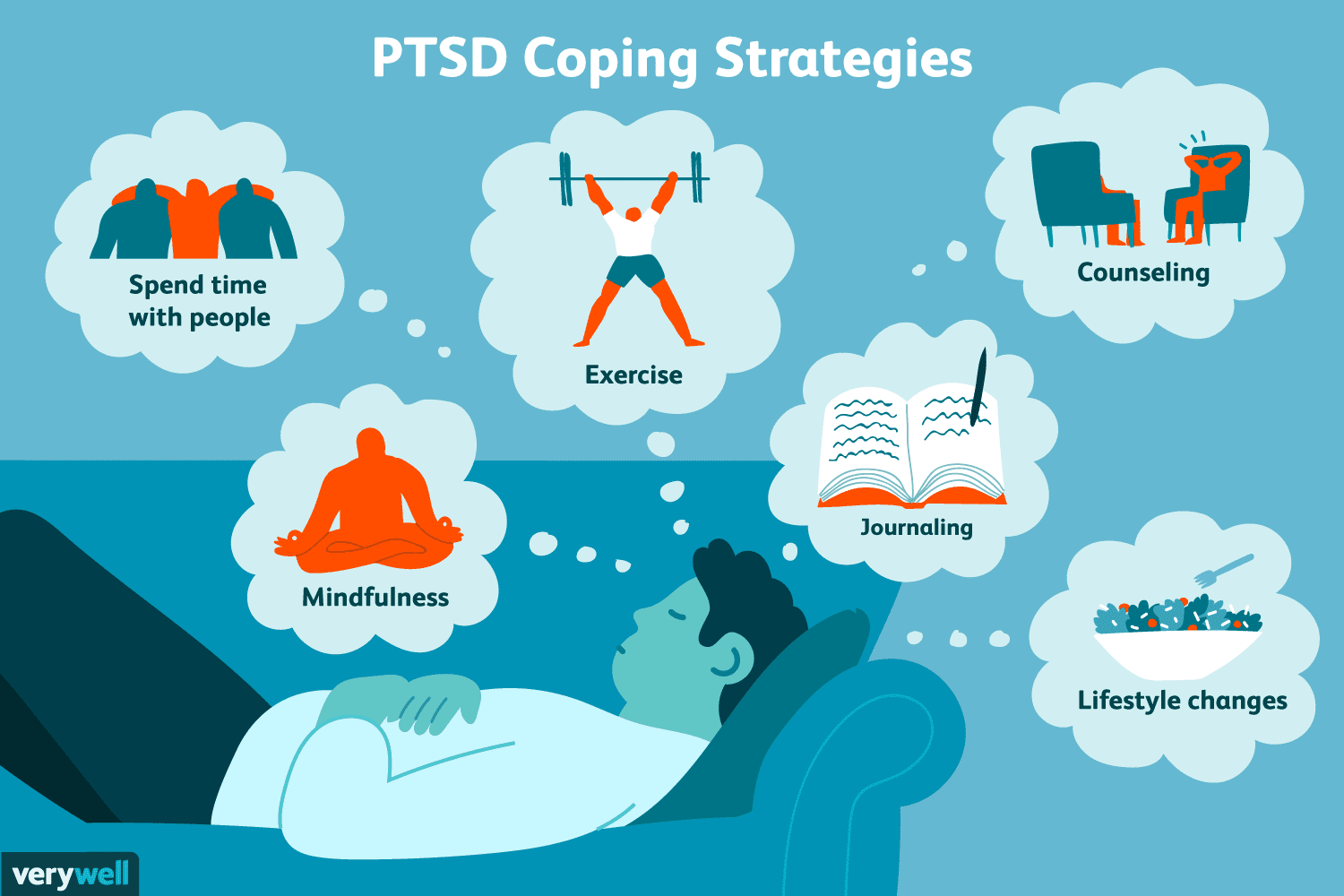

An additional component of CBT is relaxation training that is used to reduce the activation in the amygdala and the subsequent sympathetic nervous system response of fight-flight-freeze. The methods include various types of breathing techniques, muscle-focused relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and grounding skills. Also found to facilitate relaxation are meditative movement therapies (e.g., yoga and tai chi) and light-to-moderate aerobic exercise (with significant research-proven benefits for the brain and the body in general), both of which I typically suggest to clients. For those who wish to incorporate them into their new routines, we work together on devising an action plan and schedule that may help with motivation and accountability.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

CPT is a short-term (8-15 sessions), evidence-based CBT protocol specifically designed for trauma treatment. The usual CBT tools (described above) are tailored toward the focus on getting people unstuck in their trauma recovery process. Features of CPT include teaching clients skills that will help them identify how they have been interpreting why the trauma happened and its consequences; learn skills to examine and challenge the stuck points; examine beliefs about oneself, others, and the world in light of the trauma; address changes to safety, trust, power/control, self-esteem, and intimacy; as well as to increase the ability to develop independently a healthier approach to beliefs and emotions.

Psychodynamic Therapy

This approach recognizes the complexity of mental life and therefore addresses underlying psychological forces that may affect who you are. It is an approach that considers the relationship between past and present and helps you understand the why behind your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, including the root of self-defeating patterns. This enhanced self-awareness is thought to be behind the fact that clients who receive psychodynamic therapy continue to improve after treatment ends.

What else can you do?

In addition to talking to a doctor and/or a psychotherapist, consider the following:

- Be patient with yourself, with the medication, and with talk therapy

- Take advantage of your support system (family members, friends, clergy, etc.)

- Tell your family members and friends about things that may trigger your symptoms

- If you have returned to work and have supportive colleagues, consider telling them about your triggers

- Try aerobic exercise to help reduce stress

- If possible, spend time outside in nature and in the sun (unless these are currently your triggers)

- Set realistic goals and be kind to yourself

- Break up large tasks into small ones and set priorities

- Consider joining a peer support group

- Avoid alcohol and illicit drug use

If you are in a crisis

- Call 911 or go to the nearest hospital emergency room

- Call the Georgia Crisis & Access Line at 1-800-715-4225

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255)

If someone you know has PTSD, ASD, or an Adjustment Disorder

- Learn about the disorder so you can understand what they are going through

- Offer emotional support, understanding, patience, and encouragement

- Listen carefully to what they have to say about their feelings and symptoms, especially what triggers them

- Invite them to activities; don’t push too hard if they say no, but continue to extend invitations

- Suggest getting help and remind them that with time and treatment, things will get better

- Never ignore comments about death or wanting to die (see “If You Are in a Crisis,” above)

Content based in part on the following two public domain sources:

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013

- National Institute of Mental Health publications