Brain & Trauma

When we consider the mental functioning of someone who has been traumatized, we usually think of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). As mentioned in the Overview section of Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, up until the publication of the DSM-5 in 2013, PTSD was classified as an anxiety disorder. This change was made because the authors of the DSM-5 recognized that only some individuals with PTSD experienced mostly anxiety-based symptoms. While this is true, exposure to a traumatic event causes an initial reaction in the brain—and therefore throughout the body—that is reminiscent of how anxiety disorders begin and maintain.

As a reminder, PTSD symptoms are grouped into the four categories of intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitive process and/or mood, and reactivity. Symptoms typically begin within the first 3 months after the traumatic event. While some individuals reach full recovery within 3 months (about 50% of adults do), others may remain symptomatic for more than a year, for multiple years, or at times even for decades. The more time someone spends having PTSD symptoms without getting professional help, the more these dysfunctions become entrenched.

When we experience the possibility of or actual immediate danger, various parts of the brain—including the limbic system and the brain stem—work in unison to activate the fight-flight-freeze instinctual response. The sympathetic nervous system shifts the body into survival mode, increasing breathing and heart rate and decreasing all non-essential functions. At the same time, this reactive process overrides the “thinking brain,” that is, the areas of the forebrain involved in higher-order functions.

Once immediate danger (or our perception of it) passes, the parasympathetic nervous system takes over and brings the body back to a balanced, nonemergency state. At that point, the brain is restored to the normal structure of top-down control in which the cerebral cortex, the most advanced part of the brain, is once again in charge. However, when traumatizing experiences are severe or chronic and PTSD develops, the brain and the body never quite return to a normal state.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

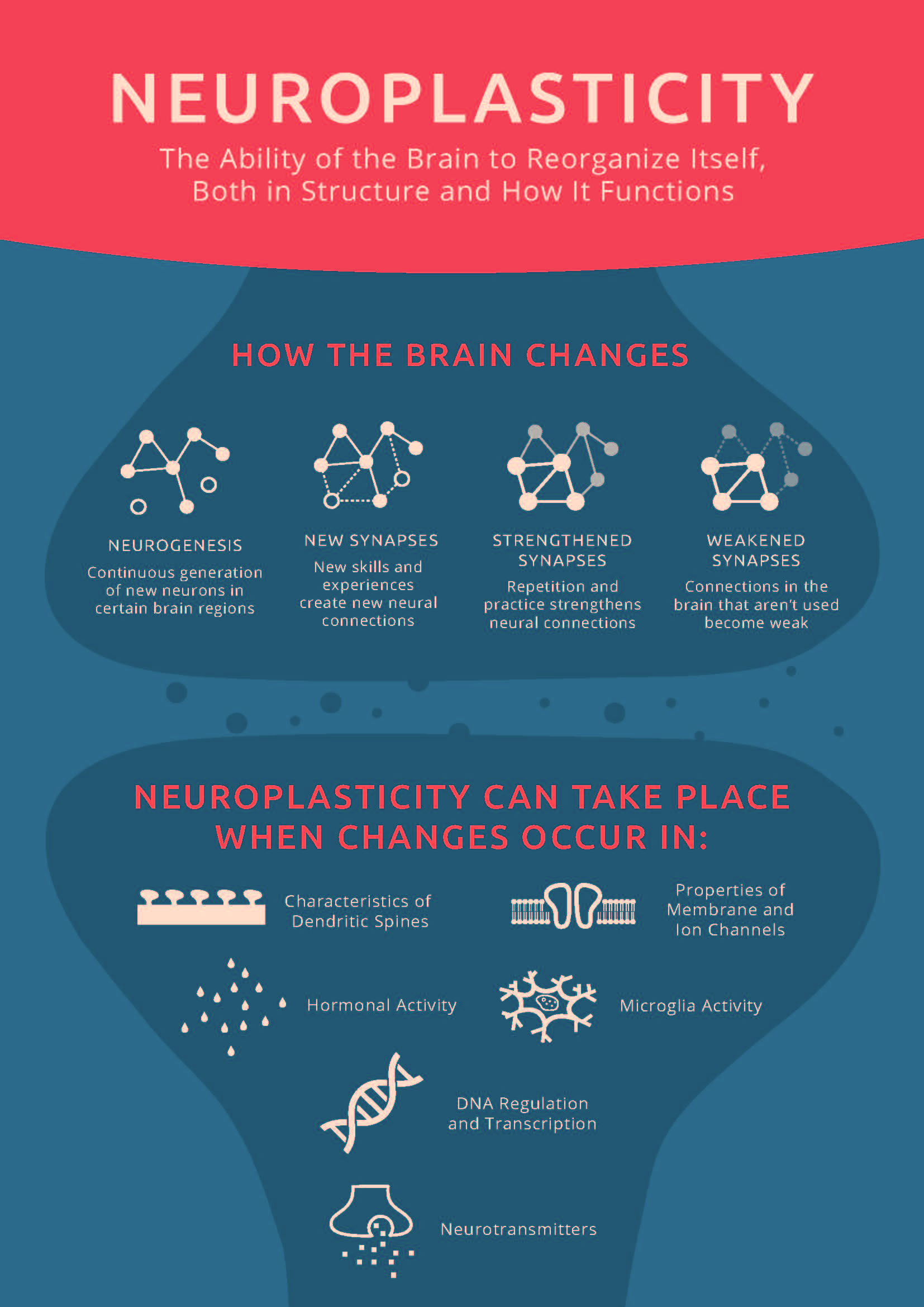

PTSD causes biophysiological changes in the brain. This is the “dark side” of neuroplasticity (keep reading to the end of this section for the “bright side”). Research have discovered that a number of structures in the brain undergo change. In summary, some become underactivated while others are overstimulated. The following table describes four of the most important changes. Corresponding PTSD symptom categories are listed for each brain structure.

| UNDERACTIVATED | OVERSTIMULATED |

|---|---|

| Hippocampus in the limbic system* Intrusion, Arousal & Reactivity, Negative Cognition & Mood (e.g., intrusive memories, flashbacks, exaggerated negative beliefs) |

The amygdala in the limbic system Arousal & Reactivity, Intrusion (e.g., persistent negativity; hypervigilance; exaggerated startle response; irritability; sleep issues; magnification of the negative effect of intrusive memories and dreams and of distress response to triggers) |

| The prefrontal cortex in the frontal lobes* Intrusion, Negative Cognition & Mood, Arousal & Reactivity (e.g., intrusive memories, flashbacks, persistent negativity, poor concentration & attention, reckless behavior) |

Anterior cingulate cortex in the frontal lobes Negative Cognition & Mood, Arousal & Reactivity (e.g., persistent negativity, lack of participation in activities, irritability, reckless behavior) |

*Magnetic Resonance Imaging has shown that the volume of the hippocampus and certain parts of the prefrontal cortex may actually shrink in cases of chronic PTSD.

In addition to these changes in the brain, the body also suffers from constant elevation of stress hormones. The overstimulated sympathetic system keeps the organs in a chronic state of alertness, which fatigues the body and causes numerous negative effects.

One final word about the concept of neuroplasticity that was mentioned above. The seriousness of the possible changes to the brain may appear like a lost cause that leads to permanent dysfunction. However, researchers have found that psychotherapy and body-centric approaches can help reverse these negative biophysiological processes and rewire the brain back to health. Positive outcomes include not only restoration of the structures that lose volume due to trauma (e.g., the hippocampus), but also return of the nervous system to its healthy, balanced functioning.